The relationships between investment managers and corporate management is an especially common example of the principal–agent relationship. This problem may occur, for example, in the governance of the executive power, ministries, agencies, intermunicipal cooperation, public-private partnerships, and firms with multiple shareholders. The multiple principal problem is particularly serious in the public sector, where multiple principals are common and both efficiency and democratic accountability are undermined in the absence of salient governance. As a result, there may be free-riding in steering and monitoring, duplicate steering and monitoring, or conflict between principals, all leading to high autonomy for the agent.

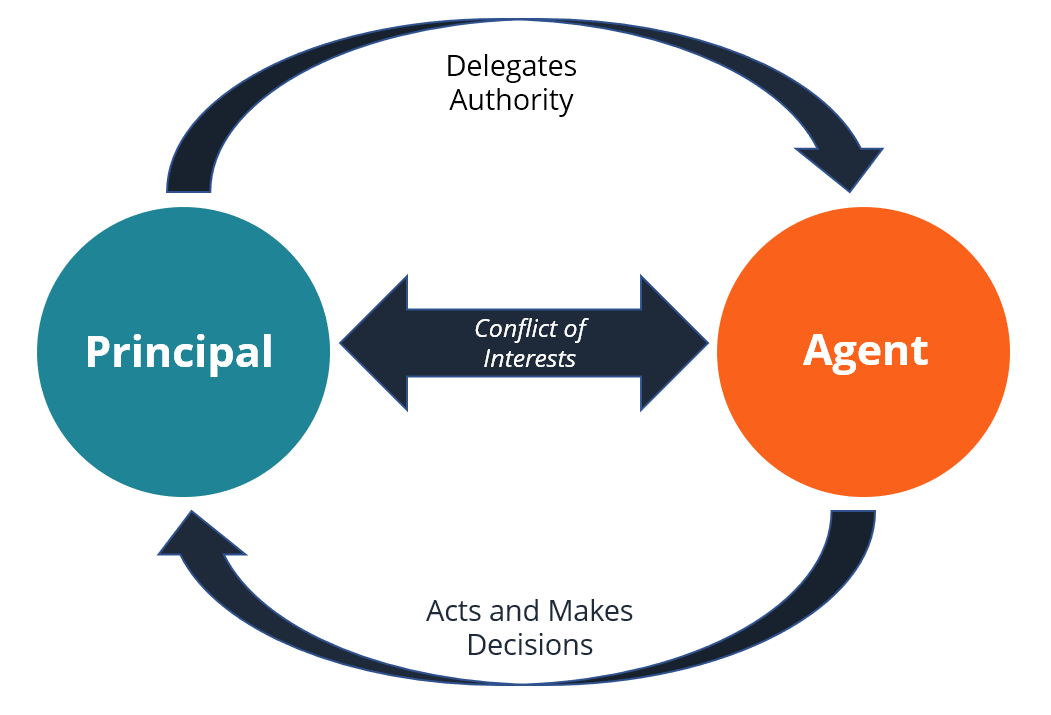

When one agent acts on behalf of multiple principals, the multiple principals have to agree on the agent's objectives, but face a collective action problem in governance, as individual principals may lobby the agent or otherwise act in their individual interests rather than in the collective interest of all principals. The agency problem can be intensified when an agent acts on behalf of multiple principals (see multiple principal problem). The deviation from the principal's interest by the agent is called " agency costs". Often, the principal may be sufficiently concerned at the possibility of being exploited by the agent that they choose not to enter into the transaction at all, when it would have been mutually beneficial: a suboptimal outcome that can lower welfare overall. The principal–agent problem typically arises where the two parties have different interests and asymmetric information (the agent having more information), such that the principal cannot directly ensure that the agent is always acting in their (the principal's) best interest, particularly when activities that are useful to the principal are costly to the agent, and where elements of what the agent does are costly for the principal to observe (see moral hazard and conflict of interest). In fact the problem can arise in almost any context where one party is being paid by another to do something where the agent has a small or nonexistent share in the outcome, whether in formal employment or a negotiated deal such as paying for household jobs or car repairs. Consider a legal client (the principal) wondering whether their lawyer (the agent) is recommending protracted legal proceedings because it is truly necessary for the client's well-being, or because it will generate income for the lawyer.

: 725, 741 Issues can also arise among different types of management.Ĭommon examples of this relationship include corporate management (agent) and shareholders (principal), elected officials (agent) and citizens (principal), or brokers (agent) and markets (buyers and sellers, principals).

: 725, 741 As shareholders are dis-incentived to intervene, there are fewer checks on management. Issues also arise when companies have an incentive to become increasingly deferential to management that have ownership stakes. This dilemma exists in circumstances where agents are motivated to act in their own best interests, which are contrary to those of their principals, and is an example of moral hazard. The principal–agent problem, in political science, supply chain management and economics (also known as agency dilemma or the agency problem) occurs when one person or entity (the " agent") is able to make decisions and/or take actions on behalf of, or that impact, another person or entity (the " principal").

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)